Two weekends ago, I had the honor of being a member, along with my friend Erica, of the first group of people from the public welcomed back into Jawbone Flats of the Opal Creek Wilderness, in Oregon, on an overnight trip. To be clear, the area is still considered a burn zone and is not open to the public, just to people on the guided group trips. This was the first of six overnights they are offering this summer to conduct research and foster conversations about what this sacred ground could be after the forest was ravaged by the Beachie Creek Fire in 2020 and almost all of the structures were destroyed by the flames, except for one of the larger cabins that was miraculously left unscathed.

But, the Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center organization remains intact and in the past five years has not only worked to restore access to Jawbone Flats and gather a team dedicated to rebuilding a thoughtful and sustainable new vision, but has also continued to inspire youth with outdoor programming by offering backpacking trips all over the state and outdoor school at Silver Falls State Park.

For thousands of years, the confluence of creeks that would eventually be known as Jawbone Flats has drawn people to its embrace. Long before any European footsteps echoed through these Western Cascade canyons, the Santiam Molalla and Santiam Kalapuya made summer pilgrimages here, following ancient ridgeline trails to hunt, forage, and trade beneath the towering old-growth giants. The 1860s brought different kinds of seekers, miners chasing dreams of gold and silver through these rugged valleys, their aspirations ultimately yielding more in hope than riches. In Jawbone Flats you can still see abandoned Model T's among the bracken from the early 1900s.

When conservationists like George Atiyeh recognized this as one of the last strongholds of low-elevation old-growth forest in the 1980s, they fought to transform it from extraction to preservation, creating a place where thousands of school children would discover the ancient forest's secrets each year. Through Indigenous stewardship, mining booms and busts, conservation battles, and educational awakening, this remote canyon has remained what it has always been, a place that calls to people, that changes them, that endures even when catastrophic fire sweeps through, leaving behind both loss and the promise of renewal.

On June 28th, 2025, our group of 10 met in the parking lot of the Oregon Department of Forestry. We were met by our guide, Elizabeth, who unlocked the gate of the service road and drove us to the trailhead and began the 3-mile hike in with us to Jawbone Flats wearing our hard hats to protect us from any falling limbs or trees. Along the way, she pointed out wild blackberries, salmonberries, and thimbleberries growing among the thick bracken that has grown back over the past five years at the feet of the towering charred remains of the trees. "You can eat them all!" she smiled, and so I did! The blackberries were my favorite, and so the hike was slow, hiking and picking.

Among our group was a nature writer, a married couple who are both sustainable architects and their 10-year-old son, and four friends who have many, many years of nature experience between them. Along the way, we shared stories about our experiences at Jawbone Flats before the fire. Erica and I went on a yoga retreat there in 2015 and remembered standing in front of our cabin and practicing yoga with our teacher, Angelina, in the commissary, both buildings now reduced to ash. In between yoga sessions, we did a nice hike to the Opal Pools during our free time on the retreat and got caught in a sudden downpour and were drenched to the bone when we made it back to the cabin. We remembered doing yoga in the meadow on the last day and sharing reflections on the magic of connecting with other yogis in an ancient forest. Everyone had stories to tell, of being connected to nature and to their essential human selves.

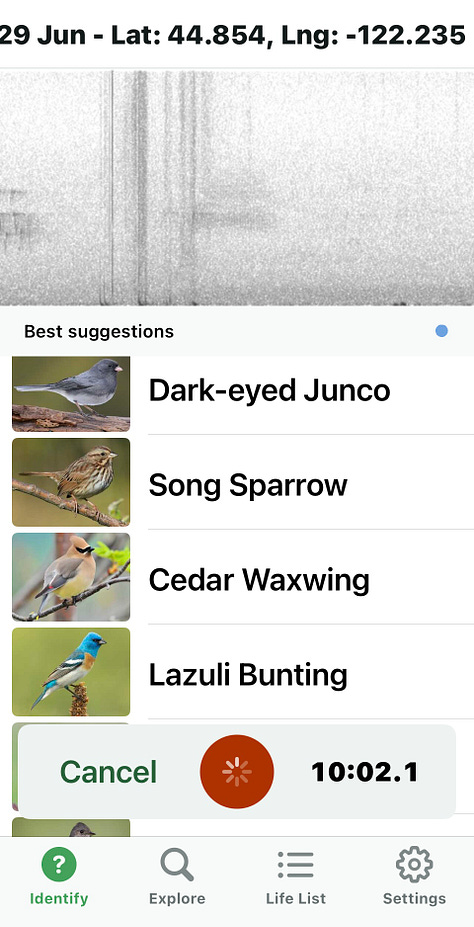

Ten years later, we are back on this overnight, and the theme is birds. Many birds come back to burn zones, following the bugs that love to dine on dead trees, to eat the bugs and the berries that flourish in the bracken. At dinner that night, the scientists leading the research explained what we would be doing the next day, using an app called Merlin Bird ID to identify bird species based on their songs that are in different designated plots in the forest. I am a science nerd at heart, and learning that we were actually going to go out into the field to help collect data for real science was thrilling.

The next morning, after breakfast and packing up, we set off, splitting into groups when we reached the plots. Erica and I trekked through the bracken and over downed, charred logs with the rest of our group until we reached the plot. We each took a direction on the perimeter of the circle facing out with our Merlin bird apps ready to go. We started recording and stayed silent for 10 minutes scanning the skeletal remains of the forest for any bird activity. The app identifies each bird as it sings, adding them to your list for the duration of the recording. As the same species of bird sings again, the bird will light up on the list to indicate a new song instead of a new species. After 10 minutes, we made a complete list of the bird species from that plot for that 10-minute period from all four lists in our circle. Then we regrouped with the other teams from the other plots and compared lists. We did this whole process again in a different area of the forest. The first area was replanted in the 1940s. The second area was mostly old-growth forest.

I have to say that the app changed the way I hear birds. I used to hear them as "birds", but now I am hearing them as separate individual creatures, each living its life and doing its part to bring this forest back to life.

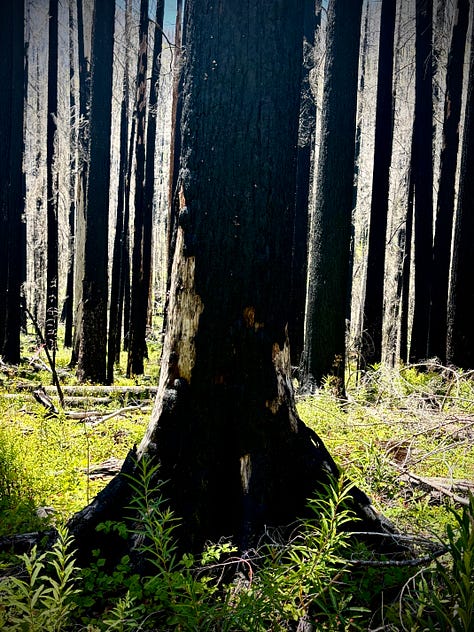

I am not sure what I expected from spending time in a forest that had been devastated by fire, but I did come to feel that devastated is not the right word at all. Yes, it is devastating that almost all of the structures of Jawbone Flats were destroyed, but in the forest, fire has always been part of the story. The forest has an ancient wisdom about cycles of renewal that we often forget in our human timelines. Fire, which seems like pure destruction to us, is actually part of the forest's eternal rhythm of making room for what comes next. The forest's eternal wisdom and the cooperation among the members of its ecosystem - the lichen, plants, insects, birds, fungi, and other animals - allows it to come back to life.

But, just like the forest coming back to life and adapting, the Opal Creek organization is adapting and growing in new ways with new intentions for education, safety, and sustainability. Yes, climate change is going to make forest fires more likely and severe, but we will not give up on this sacred place. We will learn from the forest's ancient wisdom about renewal and growth, about making room for what comes next. We will continue to be called to this place that changes us, that teaches us about resilience and the power of beginning again.

Standing in that circle with the Merlin app, listening to individual birds singing their part in the forest's return, I realized that this is how all meaningful growth happens - not despite loss, but because of the space that loss creates. The bracken growing thick at the feet of charred trees, the berries flourishing where old structures once stood, the birds returning to feed on insects that thrive on dead wood - all of it part of an ancient dance between ending and beginning, between what was and what is becoming.

Perhaps the most important lesson is that growth often requires us to let go of what we think we need to hold onto, to trust in the wisdom of cycles we don't fully understand, and to listen carefully for the new songs that emerge from the seeming silence of loss. Sometimes growth is not possible without making room for it.